“These are my eyes now,” Charbel says, showing his hands. The hands of this man tell a story of hard work in the fields. A story framed by tough, rough skin etched with grooves resembling the topographical lines of the land he has tended for years.

“Don’t move anything here, because I’ll never find it,” he warns anyone entering his home. Chaos, disorder—it’s absolute darkness for him.

Charbel wakes at 5 a.m., long before sunrise. For twenty years he has seen only darkness and blurred white. Yet he knows when the day begins, even though the colors and shapes of the sunrise now exist only in his memory. He starts making tomato paste from what he picked in his garden the day before. His customers love it. In the back of the vegetable shop, he lays out his tools. He touches each one multiple times to remember where it belongs. He examines every piece of produce with his hands. Each is delicately cut into pieces, his sharp knife gliding over the wooden board. Every motion is measured, turning the caution of a blind man into a meaningful ritual. When the pieces go into the large mixer, Charbel’s fingers search for the edges, check the lid’s attachment and latches. Only when he is sure everything is in place does he press the switch.

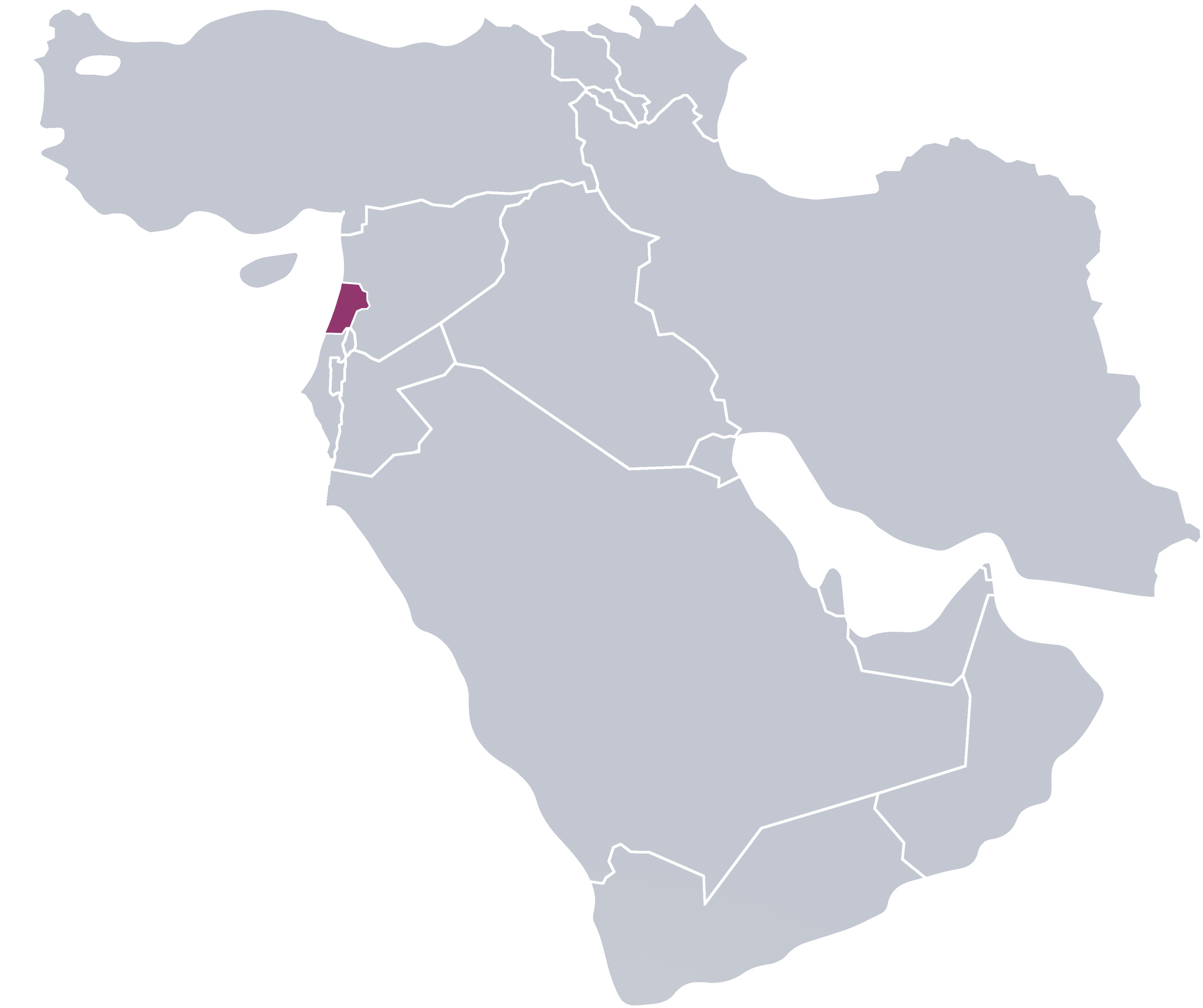

Together with his brother Doumith, Charbel has spent most of his life here, on the outskirts of Qlayaat in the mountains near Beirut. Here they run the vegetable shop. Here, at age 40, both lost their sight—Charbel first, Doumith a few years later.

“I knew I would stop seeing. You can’t prepare for it. There’s no way to see the world in advance. Losing your sight takes away the beauty around you and your independence. Move my cane I use in the garden to pick tomatoes, and I won’t get there,” Charbel says.

He insists that happiness comes when life has meaning. For both brothers, that meaning is found in the garden and the vegetable shop.

“Responsibilities and hard work don’t wait for inspiration. You just have to do them. People don’t need to ask whether we’re okay—they come into the store and see. When nothing is missing from the shelves, it means we’re doing fine.”

“What do you dream of?”

“That illness won’t take away the purpose of my life. Doctors gave me six or seven years. That was fifteen years ago,” Charbel says, smiling like someone who has outsmarted fate.

Charbel suffers from a serious and burdensome intestinal disease. For a long time, buying the prescribed medication was only a dream—just as it is for more than 80 percent of chronic patients in Lebanon. The country’s economic collapse has made daily life a journey through darkness, the kind Charbel calls absolute. You have helped him. Thanks to you, he already has his next dose of medicine. We make sure he still feels needed—by buying vegetables from him to include in packages for other beneficiaries in Lebanon.

“I’m happy. My work has meaning. I know how hard life is for others. I’m glad my vegetables reach those who need them most,” he says.

The life of Charbel and Doumith is not a tragic anecdote or a sentimental picture. It is a simple sequence of duties, rituals, and small victories. In these repeated gestures lies a sense of purpose that no one can take away.