“The good shepherd knows his sheep, and they know him.” A truth known since biblical times comes alive here, in practice, with Doumith—a good shepherd from Lebanon.

The farmyard drops steeply down a Lebanese hillside. Beyond the fence, by an unpaved road, stands a building you reach by walking down steps so low that the roof beams barely rise above street level. The front of the building is Charbel’s veggie stand; the back, opening onto a cascading garden even lower down, is where the brothers live. Below the house are greenhouses, grapevines climbing over makeshift roofs, a sheep pen, a chicken coop, rainwater tanks, and a tangle of gutters, pipes, and hoses—because water is precious here. For a blind person, the farm could be a dangerous maze. For Charbel and Doumith, it isn’t. They know every corner by heart and move around with ease—almost daringly.

“Between black and white, there are many colors to see. Blindness makes things radical—everything suddenly becomes binary. Objects are either where you expect them to be, or they aren’t. There’s no nuance, no delight or disappointment in the colors the world chooses for different moments.” Doumith knows what he’s talking about—he lost his sight shortly after turning forty. He misses it, but he doesn’t despair.

He lives with his brother Charbel, who lost his sight soon after him for the same genetic reason. Both decided that instead of becoming bitter, withdrawn, or waiting for others to do things for them, they would live as if nothing had changed. Doumith ties a scarf around his head, reaches for his stick, and—dignified like a bishop with a crozier—goes out to meet the sheep. He enters the pen, changes the water in the trough, gives feed and hay. The flock comes alive. The bells around their necks have their moment. He waits until they’re ready to set off.

They leave the pen. Not one dares to overtake its shepherd. They climb up to the road. Doumith opens the gate, sets the direction—and suddenly everything changes. He loses the certainty that comes with the familiar, learned space of home. Now most of the sheep walk ahead of him, as if sensing a need to switch roles. Guided by the sound of the bells of his leading sheep, he walks with them for hours. They return home before dusk.

“A blind person has to trust, and a shepherd has to value his sheep. They know what they need. A shepherd isn’t there to dominate them or always know better,” Doumith explains—a truth about shepherding that could be printed in the margins of the Bible.

“What motivates me is caring for others. I like people, I like animals. As long as I can do something for them, my life has meaning,” the conversation by the sheep turns philosophical. “I know that the more I give of myself, the more good comes back to me. When I stopped seeing, I suddenly stopped going out and lost contact with people I used to meet often when I worked as an electrician. Now they gladly come to our shop for vegetables, and many of them help us. Even a shepherd needs to be a sheep in a larger flock sometimes,” Doumith says with a smile.

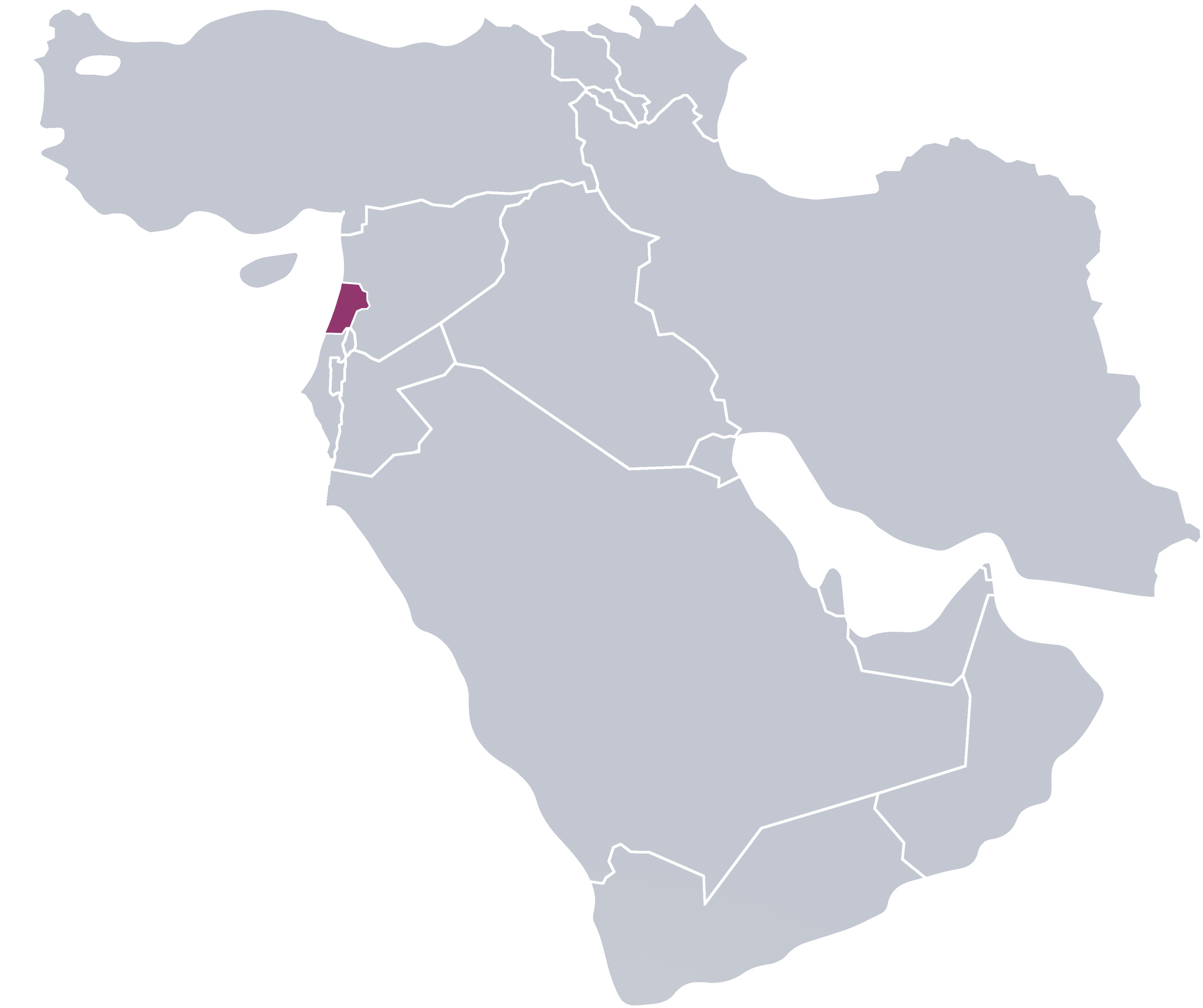

“My guide through the darkness of life in Lebanon is Dr. Harouny. Everyday life here isn’t easy. The lack of color is something even those who can see understand well—after all, we lack almost everything. We don’t have electricity or running water. We can’t afford basic products, and the income from our veggie stand barely covers the garden’s needs. Thank you for the meds for my brother. Thank you for your help.”